Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus stands as a defiant resurrection, a manifesto of suffering that transcends the mere act of survival and becomes something far more harrowing. At its surface, the poem speaks of death—death rehearsed, performed, and conquered—but beneath the bravado, there’s a desperate undercurrent that mirrors the fragile line between life and the endless desire to break free from it. There’s a terrible irony here: a woman who dies and revives on command, as though her agony is not only a spectacle but her one unshakable talent.

The speaker is both victim and perpetrator in a cyclical ritual, dragging herself back from the brink of death only to prepare for it again, as if this process is the only constant in her existence. The macabre show she stages for her audience—"Gentlemen, ladies"—is unsettling, but it’s also brutally personal. Here, Plath wields death like a performance piece, mocking those who watch her, who expect something final and conclusive. But there is no finality, only the endless return, the relentless cycle that embodies the human condition itself: the fight, the fall, the rise, and the hollow repetition of it all.

She is not spared for her strength or her will but dragged back into existence, where she remains painfully self-aware. The line between life and death blurs, and in that space, she doesn’t find peace, but something far darker, a despair so visceral that it becomes tangible.

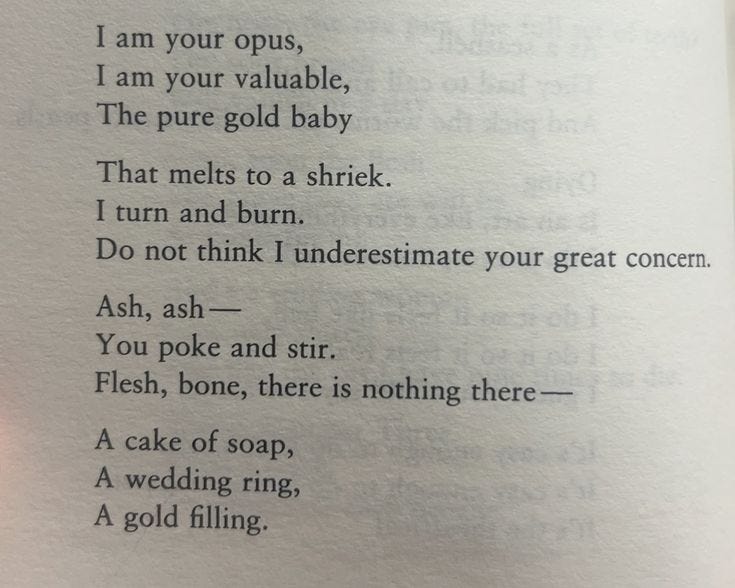

Plath’s speaker exhibits a rage that transcends personal suffering; it is a cosmic fury aimed at the very idea of existence. The persona burns with anger at the world for keeping her alive, for forcing her into this grim resurrection. The imagery of being stripped and rebuilt, reduced to the "peanut-crunching crowd" observing her agony as though it’s some grotesque form of entertainment, speaks to the commodification of her pain. Her suffering is not private, but public, turned into a spectacle for the masses to consume, as if her body is an object that belongs to everyone but herself.

And yet, there is power in her performance. Each return is a statement, not of survival, but of reclamation. In rising from the ashes, she is reborn in fury, not grace. There’s a vindictive pleasure in the repetition, in defying the forces that seek to silence her. She dares the world to kill her again, knowing full well that she will always rise. “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.” These final lines aren’t just about vengeance—they’re about transformation. Death does not diminish her but magnifies her strength, her ability to endure and weaponize her suffering.

What lies at the heart of Lady Lazarus is not merely a personal struggle but a confrontation with the existential absurdity of human existence. The poem challenges the idea of life as a gift, suggesting instead that life and death are a performance, an eternal back-and-forth that strips away any illusions of meaning. The speaker’s multiple deaths become metaphors for the countless ways we are forced to die and be reborn throughout our lives—emotionally, spiritually, psychologically—each time leaving us a little more fragmented, yet somehow fiercer.

The speaker's final, triumphant assertion that she rises "with [her] red hair" feels both monstrous and divine, a phoenix not of mythic beauty but of a terrifying will. She consumes the very men who watch her, the world that strips her bare, turning the gaze back on those who demand her resurrection. It is not enough to survive. To survive is to become something more, something ferocious, something that devours. Plath doesn’t offer a path to salvation or enlightenment—there is no peace in Lady Lazarus, no serene afterlife awaiting those who suffer. There is only the rage that burns hotter with each death, the relentless refusal to remain silenced.

Plath weaves together death, rebirth, and the violent reclamation of identity in a way that distorts the very nature of resurrection. It is not about hope, not about redemption. It is about survival as resistance, about the sheer fury that drives a person to rise again, not because they want to, but because they refuse to be erased. Plath’s speaker doesn’t offer solace; she offers a mirror to the darkest corners of human endurance, where death is not the enemy.

Excited to read your view on other poem